How games and apps manipulate and monitor children

Profiles are created for children to sell advertising and to keep their interest over time. In the worst case, vulnerabilities in children can also be exploited in an unethical way, says Finn Myrstad, Senior Adviser of the Consumer Council (Forbrukerrådet).

Choose language in the Google-box below. Some translations may be flawed or inaccurate.

The vast majority of free apps track children’s activities, says Finn Myrstad, Senior Adviser of the Consumer Council. Contact lists, location data, and other information that should have been private are collected for the purpose of making money by the app providers.

“This may involve information retrieved from the mobile phone or the actual use of the app. Among other things, children’s interests and how they react while playing different games are mapped. This can be used to provide children and young people with customized advertising. For example, advertising interruptions when watching YouTube where the commercial is targeted to the children’s interests,” says Myrstad.

![]()

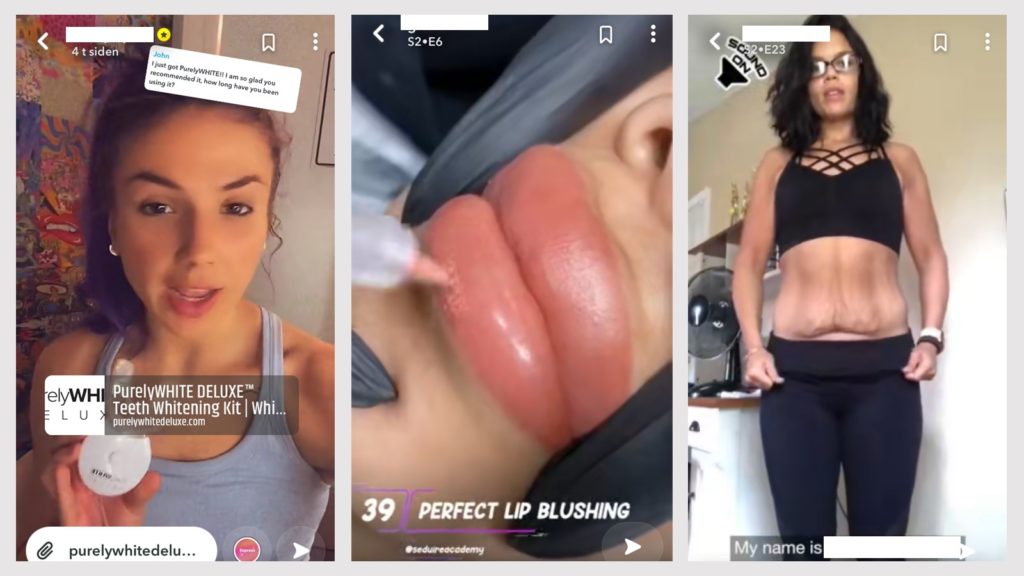

This type of technology has become quite advanced and can abuse vulnerabilities in the user. In addition, it distinguishes poorly between adults and young consumers.

“We also know from surveys that young people are exposed to high advertising pressure. There may be advertisements for dieting, muscle building, and cosmetic surgeries. It plays with the children’s insecurity and vulnerability, which in turn can reinforce negative thoughts and more sales of similar products,” Myrstad points out.

(Foto: Screenshot from Instagram)

Not all data collection is equally bad

Sometimes apps collect user data to improve their own services or to help the app remember the user’s progress in the game.

“The providers make money by keeping children and young people on the platform or in the game as long as possible. Therefore, instruments are also used to keep users’ attention. The goal is to get children and young people “hooked on the service.” Studies have shown that what makes people hooked is the so-called engaging content. And what is it that engages them? The posts that raise anger, strong emotions, and the like,” Myrstad explains.

It also means that the algorithms adapt and you risk getting more extreme content.

“If you are interested in diet, you get more of that type of content. And the content can become more and more extreme and may, for example, turn towards anorexia. Surveys show that both boys and girls see content that revolves around everything from muscle building to eating disorders,” says Myrstad.

The Senior Adviser also points to a survey conducted by Instagram (Meta) which shows that 1 in 3 girls have a poorer self-image (BBC article) after using their social media app.

“The algorithms fail to distinguish between what is engaging in the form of educational content and what is harmful. Technology only perceives that children and young people look at something for a long time and react to it,” Myrstad emphasizes.

Predicts your interests and needs

When you install a new app on your phone, it asks for more permissions. The mobile features can be used for various purposes.

“For example, accessing your contact list can help the app understand both who you are and who your friends are. If you have several friends who belong to a religious minority, for example, it is easier for the app to estimate that you probably belong to the same religion. The same decisions the app can make based on you and your friends’ political views, sexual orientation, and more.”

“This is very private information and especially for children and young people who are in a vulnerable and exploring phase, this can be problematic. There could be major consequences if this information gets out in some way,” says Myrstad.

App providers know where you go to school and work, whether you see a psychologist a few hours a week, or if you visit a hospital.

Another type of information that apps often ask for is location.

“Often this information is as close as 2 meters from where you are at a given time. Then the developers can find out more about where you go to school or work, whether you see a psychologist a few hours a week, or if you visit a hospital. Thus, sensitive profiles about the lives of individuals and groups can be created. For example, you may get targeted advertising for medical products if the app estimates that you are depressed and go to a psychologist,” says Myrstad.

Camera access is like handing out fingerprints

Several apps also request access to your mobile phone’s camera and photo gallery. Here there are privacy dilemmas not only for the pictures you take but also for the file information associated with the picture.

“Inside the image file, there is information about where the photo have been taken and the time. This is something social media apps use to mark where the person is when sharing a photo. In addition, images of children can be used for indexing, and there is the technology that recognizes people across individual images. So that you are recognized wherever you are online,” says Myrstad.

The Senior Adviser compares facial recognition to sharing one’s fingerprint. Among other things, it is this technology that puts funny animal figures and filters over the face in social media apps.

“It may feel good there and then, but there is also room for abuse here. Everyone’s face is unique and over time this information can be tracked and misused in different ways. For example, if you stop smiling and the algorithm interprets it as a sign of depression. Then the marketing of products adapts accordingly. Other times, the technology is more practical, for example, to unlock your mobile phone,” says Myrstad.

(Photo: Shutterstock/Pascal Huot)

Google and Siri unlikely to eavesdrop on you

Some are worried about giving apps access to their phone’s microphone for fear of being monitored. In practice, this is unlikely, says the Senior Adviser.

“You’ve heard about the examples where someone has just had a discussion, and then advertisements pop up in the browser based on the conversation, then you may think that you are being bugged by your mobile. Most likely, this is more because algorithms have become good at predicting one’s interests and needs. The developers create profiles of us and others based on life situations – those who live close to each other, are members of the same political party, and so on. You are compared in databases with millions of people,” Myrstad points out.

In practice, therefore, the apps become good at anticipating what hits us and what we think about

“Some advertising will therefore be perceived as completely personalized for us. The problem is that this system is not very transparent. However, there are enough examples of unethical use, such as gambling addicts who are exposed to large amounts of gambling advertising. Whether you have eating disorders or gambling addiction, the content can be used to precisely reinforce such challenges,” warns Myrstad.

The algorithms can also have the opposite effect, Myrstad points out. There are several examples of people who are not sent advertising and content.

“Maybe you don’t get a housing ad or a job advertisement because you’re not considered attractive enough based on your income, gender, ethnicity, or age. In the United States, we have seen several examples of this type of practice,” says Myrstad.

Manipulative Children’s games

These types of privacy challenges mentioned so far aren’t just prevalent for social media apps and services for adolescents and adults. The Senior Adviser also considers the app My Talking Tom, which has over a billion downloads, problematic.

(Photo: Outfit7 Limited)

“This is just one example. There are many other such apps and this one isn’t necessarily worse than the others. But we saw that in this app, a lot of personal information was collected and shared with many other companies outside of the game. In practice, there was also a lot of hidden advertising for junk food and sugary drinks. In addition, there were manipulative designs in word usage and design to nudge children into using certain buttons. Among other things, to buy content,” says Myrstad.

He points out that certain games can alert users that friends have purchased game content and been upgraded, which is a form of manipulative design to get the user to spend a similar amount of money.

“We have legislation that governs this with both the Personal Data Act and the Marketing Control Act. The problem is that the data practices of the developers are hidden and thus it becomes difficult for the supervisory authorities to enforce the regulations. That is why we want a ban on surveillance-based advertising, as well as manipulative design,” says Myrstad.

Advice for parents:

Finally, the Senior Adviser has some advice for parents.

- Be careful about what permissions you give to your apps. Giving access to your contact list also gives the apps access to your friends’ personal information.

- Don’t share location/GPS unless you have to. Certain apps, such as mapping services, must necessarily have this access to function.

- Delete accounts on apps you don’t use. Do a ‘spring cleaning’ on your mobile phone every once in a while.

- Parents should test the apps their children use before the children can access them.

- Put on purchase blocks to prevent kids from buying content without permission.

- Beware of free apps, as they often collect more data and share ads than paid apps.

- If available, turn on privacy settings on your mobile phone and apps.

- Talk to your kids about personal data, manipulative design, and targeted advertising.

Top image: Shutterstock/kryzhov.

Also read:

A checklist when children start using social media

How to reduce unwanted videos on your kids’ mobile

Children see adverts for plastic surgery, alcohol, and gambling

(Translated from Norwegian by Ratan Samadder)